Many of us chase happiness but, like a dog chasing its tail, it will always be just out of reach. Happiness as an emotion is inherently transient – a fleeting feeling rather than a sustainable state. The chase can lead us to feel dissatisfied with life; like there should be something more. If we could just do more, have more, be more successful, then we’d finally be happy.

As someone who has spent decades working with high-achieving individuals, I’ve observed that dissatisfaction often stems not from a lack of success, but from an imbalance in how we engage with life that, in turn leads to a lack of meaning.

Of course, as someone born in the late 1950s, my thinking about meaning and satisfaction has been profoundly influenced by the great existentialist philosophers of the time. We are all a product of our time, after all.

For me, that time was a particularly transformative era for thinking about meaning and satisfaction, giving rise to philosophical rock stars who spoke to the deep questions we still grapple with today.

Jean-Paul Sartre was philosophy’s Elvis Presley – charismatic and revolutionary, challenging conventional wisdom about human freedom and responsibility. Albert Camus brought the cool detachment of James Dean to existentialism, teaching us to find meaning even in life’s apparent absurdity. And while she might resist the existentialist label, Hannah Arendt was perhaps its Edith Piaf – a powerful voice who, like the beloved French singer, spoke profound truths about the human condition with unflinching authenticity.

These thinkers were grappling with questions that remain vital today: How do we live authentically? How do we find meaning in life? How do we make choices that lead to genuine satisfaction?

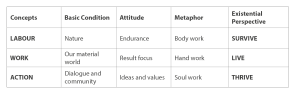

For a practical solution to these questions, we can draw insights from Hannah Arendt’s concept of vita activa – the active life – which identifies three fundamental types of human activity: labour, work, and action.

Understanding the Three Elements of a Satisfying Life

Before we explore these modern interpretations of Arendt’s framework, it’s worth “translating” these concepts for contemporary life. While Arendt’s original terms – labour, work, and action – were powerful in their academic context, today’s world calls for language that better reflects how we experience these elements in our daily lives. By recasting these ideas in more accessible terms, we can better apply their wisdom to our modern search for satisfaction.

In modern language, and with a more positive interpretation, we might redefine Arendt’s concept of labour as Mindful Movement. Its basic condition is our connection to nature and our physical existence. It requires an attitude of endurance and manifests primarily through bodywork. Labour involves an element of repetition. When we mow the lawn, for example, we know perfectly well that we will soon have to do it again. At its core, this element helps us survive and maintain our place in the natural world.

Mindful Movement involves activities that maintain our life and environment – exercise, household maintenance, cooking, gardening. These activities connect us to our bodies and the natural world, grounding us in the present moment. When we engage in Mindful Movement, we experience the satisfaction of immediate value and the deep connection to our physical existence.

Creative Doing evolves from Arendt’s concept of work. Its basic condition is our relationship with the material world. It requires a results-focused attitude but finds joy in both the process of creation and the celebration of the finished work. Through creative work, problem-solving, handwork and craft, it helps us truly live rather than merely survive.

This encompasses activities where both process and outcome matter. Whether you’re building with Lego, painting, or developing a new business strategy, the joy comes not just from the final product, but from the creative journey itself. It’s about experiencing the flow of creativity, the satisfaction of problem-solving, and ultimately producing something tangible that reflects our efforts. We often jest that whenever you see a holiday home with plenty of small annexes (orangery, pizza oven, outdoor kitchen, garages, sheds) you can be sure that the owner is a person who has retired too soon! In other words, they are missing an element of creative doing in their lives.

Impactful Thinking transforms Arendt’s concept of action. Its basic condition is our participation in dialogue and community. It requires an attitude focused on ideas and values, engaging in what we might call soul or mind work. This element helps us thrive by connecting our efforts to something larger than ourselves.

When we mentor others, contribute to community projects, or drive positive change in our professional sphere, we fulfil our need to make a meaningful difference in the world. This could be as simple as sharing knowledge with colleagues or as complex as initiating community-wide changes.

Each element represents not just an activity, but a way of engaging with the world, each with its own basic condition, attitude, and existential perspective. And by keeping them in balance, we can live a meaningful life aligned with our values and needs that can help us feel a deep sense of contentment, satisfaction and belonging.

How These Elements Create Meaning

The power of these three elements isn’t just philosophical – it’s backed by contemporary research. For example, research shows that engaging in varied types of activities significantly impacts our well-being1. Each element activates different neural pathways and satisfies different psychological needs2.

Consider three different approaches to gardening: maintaining your lawn (Mindful Movement), creating a beautiful flower garden (Creative Doing), or establishing a community vegetable plot (Impactful Thinking). While all involve working with plants, each satisfies different fundamental needs and creates meaning in distinct ways.

Studies have shown that physical engagement in repetitive tasks can reduce anxiety and improve mental clarity3, supporting the value of Mindful Movement. Creative activities have been linked to increased problem-solving abilities and emotional well-being4, while community engagement has been shown to significantly impact longevity and life satisfaction5.

Recognising Imbalances

When life feels unsatisfying, it often signals an imbalance among these three elements.

You might notice a disconnection from your physical environment, suggesting a need for more Mindful Movement. Perhaps you feel creatively stifled, indicating insufficient Creative Doing. Or maybe you’re questioning your impact on the world, pointing to a need for more Impactful Thinking.

Consider your current situation. Are you spending all your energy maintaining your environment without time for creativity? Are you pouring yourself into creative projects without engaging with your community? Or are you so focused on making an impact that you’ve neglected your immediate environment?

Different life stages bring different challenges to maintaining balance. You might be in your thirties, struggling to keep up with younger colleagues while maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Perhaps you’re in your fifties, questioning your identity and seeking ways to reinvent yourself. Or you might be approaching retirement, wondering how to create meaning beyond your career.

If you’re feeling frustrated, ask yourself:

- When did you last lose track of time while creating something?

- How connected do you feel to your physical environment and well-being?

- Where do you see your influence making a difference in others’ lives?

- What activities make you feel most alive and engaged?

Restoring Balance

The key to addressing these imbalances lies not in achieving perfection in all areas, but in ensuring sufficient engagement in each.

For instance, if you’re lacking Mindful Movement, you might start by dedicating time to cooking or gardening. If Creative Doing is missing, you could begin a project where the process itself brings joy – whether that’s crafting, writing, or problem-solving at work. For Impactful Thinking, consider how your skills and interests could benefit others or the world at large.

Remember, balance doesn’t mean equal time or expertise in all areas. Someone might find great satisfaction spending most of their time in Creative Doing, while maintaining sufficient engagement in Mindful Movement and Impactful Thinking to feel grounded and connected. The right balance is personal and may shift over time.

Implementing these changes, however, can be challenging. Common obstacles include:

Time Constraints: Many believe they’re too busy for certain activities. The solution isn’t finding more time, but rather integrating these elements into existing activities. A morning walk can become Mindful Movement, a work project can incorporate Creative Doing, and sharing experiences can transform into Impactful Thinking.

Energy Management: Different life stages bring different energy levels. Instead of fighting this, adapt activities to your current capacity. If traditional exercise feels overwhelming, gentle gardening can provide Mindful Movement. If large creative projects seem daunting, start with small, manageable creative tasks.

Social Pressure: Often, we feel pressure to focus on certain areas at the expense of others. Remember that balance is personal – what works for others may not work for you. Yes, there can be an anxiety associated with making yourself known in life.

Making It Work

Maintaining balance requires regular attention but needn’t be complicated. Here are practical approaches:

Regular Assessment: Schedule monthly check-ins with yourself to review your engagement in each area. Notice which elements feel lacking and which feel overwhelming.

Flexible Integration: Look for ways to combine elements. A community sports team combines Mindful Movement with Impactful Thinking. Teaching a craft workshop merges Creative Doing with community impact.

Adaptive Strategies: As circumstances change, be ready to adjust your approach. If physical limitations arise, find new ways to engage in Mindful Movement. If career changes affect your impact opportunities, seek new channels for contribution.

Creating Lasting Satisfaction

When we achieve our own unique balance among these elements, we develop what I call “relaxed readiness” – a state where we feel grounded, capable, and prepared to handle life’s challenges.

This balance creates resilience and a sense of control over our lives, not through attempting to control everything (which leads to anxiety), but through meaningful engagement in all aspects of life.

Through regular reflection on these elements, we can identify when adjustments are needed and guide ourselves toward greater contentment. We can move beyond the endless chase for happiness to find something more sustainable: a deep sense of satisfaction that comes from meaningful engagement with all aspects of life.

The goal isn’t perfection but rather conscious engagement with each aspect of vita activa, creating a rich tapestry of experience that leads to lasting satisfaction.

References:

1 Seligman, M. E. P. (2012). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. Free Press.

2 Davidson, R. J., & Begley, S. (2012). The Emotional Life of Your Brain. Hudson Street Press.

3 Grossman, P., et al. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35-43.

4 Stuckey, H. L., & Nobel, J. (2010). The connection between art, healing, and public health. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 254-263.

5 Holt-Lunstad, J., et al. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.