Traditionally, the ‘up or out’ model of career management has driven individual talent development within professional service firms. In addition to the practice of tutelage learning – and talent differentiation, choosing people to continue moving up the career hierarchy was not necessary. As however firms grow in scale and complexity, this informal system is less able to function. Every firm is faced with a point of differentiation as choices are made around grade promotion and promotion to partnership. The dilemma is: when and how to visibly differentiate and on what basis should this operate? This is not an idle issue. The management of firms often underestimate massively the spread of performance in groups of professionals. A typical performance variance between average performers and genuine stars in terms of visible productive output, for example fee generation, is as much as 800%. Identifying and shaping the careers of star performers is critical to the on-going performance of the firm.

Talent leadership in the firm

(A definition)

Building the capability of the individual at an accelerated pace in order to:

Build the capability of the firm in its areas of core competence in order to drive and sustain competitive advantage.

The commonly used term ‘Talent Management’, is often seen as having emerged from the book ‘The war for talent’ and is a term coined by Steven Hankin of McKinsey & Company in 1997. What is less well known is that this in itself is based in the notion of ‘core competence’ and the approach to competitive strategy of Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahalad in their article “The Core Competence of the Corporation.” (Harvard Business Review, May/June 1990, pp. 79-91.)

What is core competence?

A core competence is a deep proficiency that enables a company to deliver unique value to customers and embodies an organisation’s collective learning. A core competence creates sustainable competitive advantage for a business within a marketplace allowing the business to grow market share, margin or create differentiation.

Core competence is:

- An area of deep capability that the firm has

And

- Is visible to the client and the client values

That

- Is hard to replicate by competitors

And

- Can be used to drive competitive advantage

The acid test of a core competence? – It’s hard for competitors to copy or acquire.

Understanding core competence allows firms to invest in the strengths that differentiate them in the marketplace and set strategies that unify their entire organisation. Talent management strategies, which can result from this understanding, are aimed at accelerating the growth and depth of the core competence, thereby increasing the organisations ability to compete.

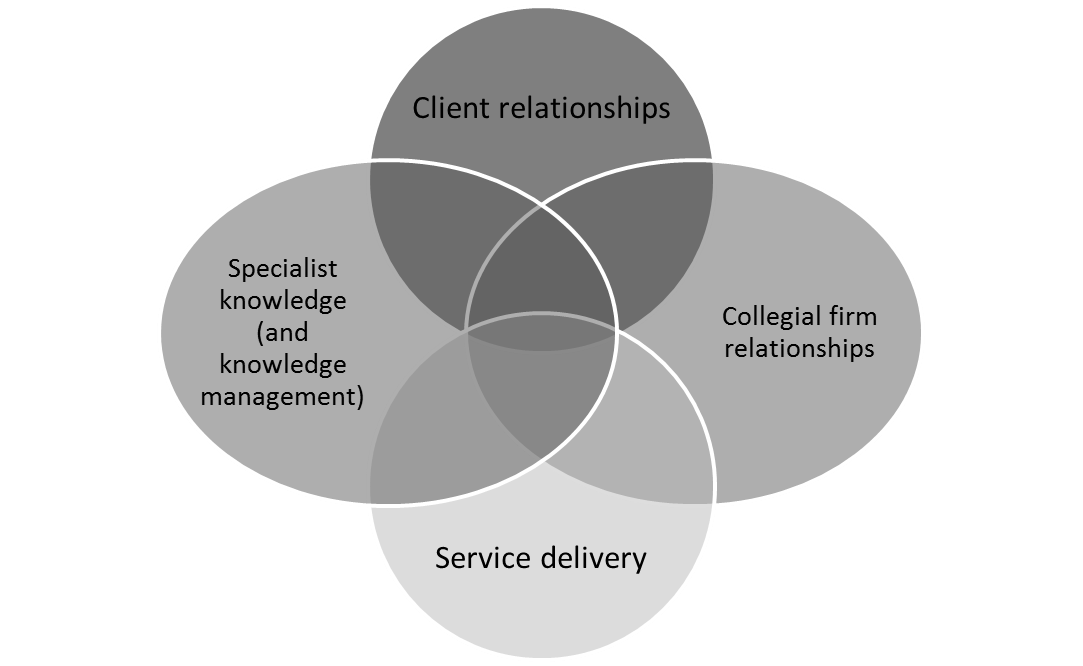

In a professional service firm, core competence will almost certainly involve iteration between four elements: service delivery, knowledge, client relationships and internal firm relationships. This basket is woven in a unique way in each firm and will determine the client’s experience of how the firm delivers its service. (See figure 1)

Figure 1: Elements of core competence in a PSF

Core competence in the development of talented people

The faster a firm can grow its capabilities, in the areas of its core competence, the bigger the competitive advantage in the market.Core competence in the development of talented people

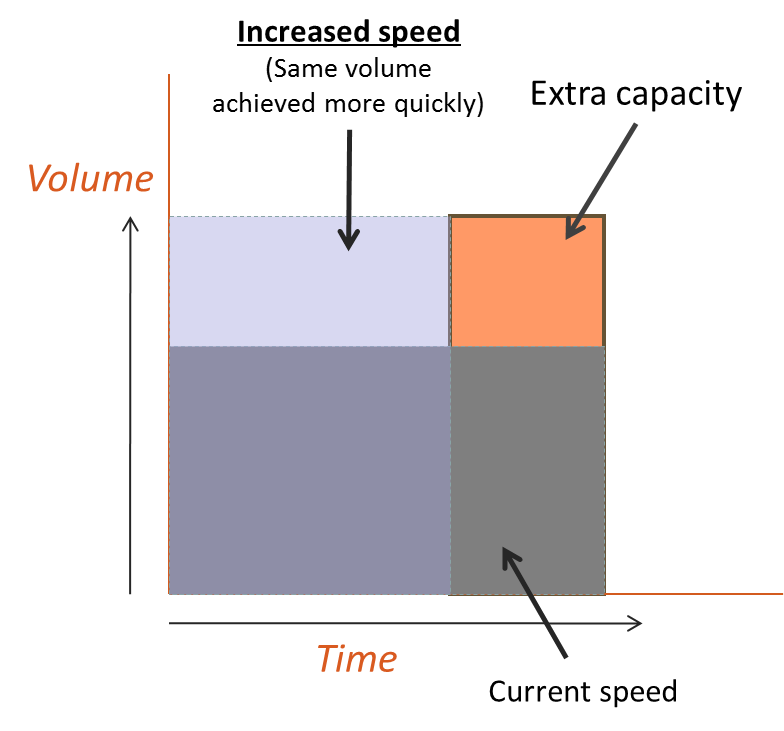

At a practical level, the task of a firm’s leadership is to accelerate the speed to experience of the most talented people in the firm. Not any experience of course – but experience in the area of core competence.

A firm can deliver a certain volume of service (and attract clients) at a certain rate. If, by increasing competence, efficiency and/or speed, without increasing resources (i.e. people) then, the firm can generate additional capacity, without additional cost. These improvements will in turn improve margin and/or revenue. (See figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Speed to experience – creating new capacity

Identification of talent

Talented people display two very different characteristics. They are high performers in terms of current work. Separately and in addition to this, they are also able to demonstrate a set of behaviors and outcomes that identify them as having high potential to grow in their careers.Identification of talent

In general terms, performance of the individual is relatively easy to see and to demonstrate in professional service firms. High performing fee-earners tend to have higher than average utilization. Their billing, client winning and work execution skills are noticed and valued. In our research with firms, we can see that firm partners have a very finely tuned sense of the performance of the people in their teams and can often rank order their people in terms of performance on an intuitive basis which is perfectly correlated to the objective performance data used by the firm.

However, a critical issue at the heart of talent development is to identify high potential in an as consistent and valid way as it is possible to identify high performance.

Our research with many dozens of professional service firms in the area of talent identification has yielded consistent and stable results. If a partner of the firm is asked who the ‘stars’ are in the firm they can tell you the answer instantly. But they often struggle to say why. However when this issue is teased out in research using critical incident and repertory grid research techniques, the result is that differentiation: distinguishing between high, average and low potential, is driven by four key components:

- Capability and skill of the person in areas of core competence (of the firm). This is the set of skills and knowledge that the client values and distinguishes the firm from its competitors. It is very unlikely to be a single, unitary skill set. In most professional firms it will be a dynamic mix of technical know-how, client handling and business management skills.

- Individual aspiration – how ambitious the person is, in terms of their personal career development. People with high aspirations will push more effort into their career development, make difficult trade-off’s in terms of their time use and typically push themselves into the path of reputation enhancing opportunities.

- Engagement – aligned with the goals, culture and vision of the firm. Highly engaged people tend to be comfortable with and committed to the firms goals, strategy and values. They like the work and they like the people they work with. They more easily commit effort to the enterprise and in associated research they offer more suggestions and ideas, are less likely to be a voluntary leaver and interestingly, also take less sick leave.

- A history of Leadership The successful initiation and sustaining of initiatives. This fourth aspect of high potential is the most difficult to identify.

Research into leadership is beset with problems as to its nature. It is entangled in its relationship with the use of formal power and authority within the hierarchical structures of managed organisations. However our research has indicated two fundamental and visible characteristics.

When we ask partners and senior fee earners what they see when they are looking at (future) leaders they consistently describe people who take personal responsibility for making things happen. They can’t stop doing this. On a wet Thursday they are the ones who are pushing the work along and are taking steps to exploit opportunities and persuade others to come along with them.

This characteristic coincides with some useful research outcomes in corporate business:

“Many companies favour job candidates with stellar academic records from prestigious schools. But AT&T and Google have established through quantitative analysis that a demonstrated ability to take initiative is a far better predictor of high performance on the job” Competing on Talent Analytics : Thomas H. Davenport, Jeanne Harris, and Jeremy Shapiro (HBR October 2012)

The second visible characteristic of leadership that we see in our work with firms is the willingness and resilience to sustain the initiative. High potential people keep going when others run out of steam. In the context of leadership they enable others to continue to follow in the slipstream they create and act as givers of confidence and behavioural role models to the people that follow them.

It is important to note that that the potential of the person is an independent variable from the person’s performance.

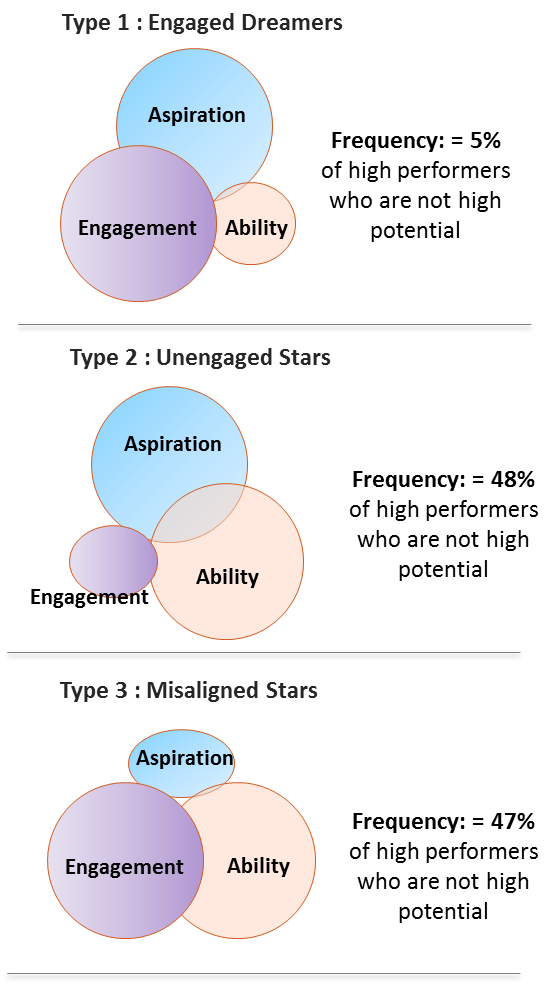

In addition, the four drivers of high potential are independent from each other. It is possible to be for example, technically skilled without the ambition to apply it, or ambitious, but unaligned to the goals and values of the firm. Unless all four drivers exist in the person, then the firm may experience a failure in the talent pipeline. See for example the results in Figure 3, of talent management failures along three of our recognised drivers (the missing one in this research is leadership, which the researchers define in a different way)

Figure 3: Talent management failures

Adapted from: CLC Talent Management (2005) – Survey of 11,000 employees at 59 global organisations

Diagnostic questions to identify potential in a fee earning professional

As part of our ongoing research into the area of talent leadership in professional firms, we have worked with partners across many firms to understand the questions that they intuitively ask themselves when thinking about the future careers of their fee-earning professionals. The result of this research is the set of diagnostic questions set out below.

Each question points at the visible behavior of the person and in the behavior of those who interact with him or her. By answering these questions about the professionals working in the firm, you can begin to move to an objective platform of assessing and identifying talent in the firm.

Expert Capable: in the core competence of the firm

Is the person…

- Recognised as an expert in the field by people within and outside the firm?

Does the person…

- Set a high bar for excellence?

- Require minimal supervision?

- Gain new skills and knowledge more quickly than peers?

Aspire: ambitious in their career goals

Is the person…

- Willing to make difficult work-life tradeoffs to support the firm?

Does the person…

- Strive to be recognised within and outside the firm?

- Aim continuously to assume more responsibility?

Engaged / Aligned: to the goals, values and strategy of the firm

Is the person…

- Well networked across the firm?

- Positive about the firm and his/her career trajectory within the firm?

Does the person…

- Pitch in to help others when they have a heavy workload?

- Work and put effort into activity aligned to firm goals?

Lead: taking and sustaining initiative

Does the person…

- Display initiative to take on responsibilities outside his/her role?

- Regularly present ideas, tactics and proposals?

- Regularly initiate activity with peers and team?

- Sustain activity beyond the normal expectations of others?

Do others…

- Go to the person regularly as a source of help and direction?

Mapping the talent landscape of the firm

In our work with professional firms, we have come across a number of techniques that enable partners and senior professionals to accurately map their people in terms of future talent.

This has two key benefits: first is to determine the stock and flow of talent. Answering questions such as: do we have the best people? Can we grow? Can we improve? The second benefit is that the mapping techniques put leaders into a position where they can give finely calibrated and targeted feedback to the people in their teams around how they are doing in their careers and what specifically, they could or should do to improve.

Sadly, many of these techniques have been bureaucratised in overly complex competency matrices. Long lists of skills and descriptors which may (arguably) be useful in stable, volume based work delivery, are entirely inappropriate to the needs of highly dynamic client facing teams. As a result they have become an administrative chore rather than a business enabler.

In the talent mapping method outlined below, I have attempted to draw back these techniques into their core use, based on our observation of partners in firms who have used them effectively to accelerate the growth of talent in their practices and firms. In the best case example we have seen, its use has led to a situation where fee earning professionals where being made up to partner at a rate of 3X that of professionals in the rest of the firm.

A PSF talent mapping core technique

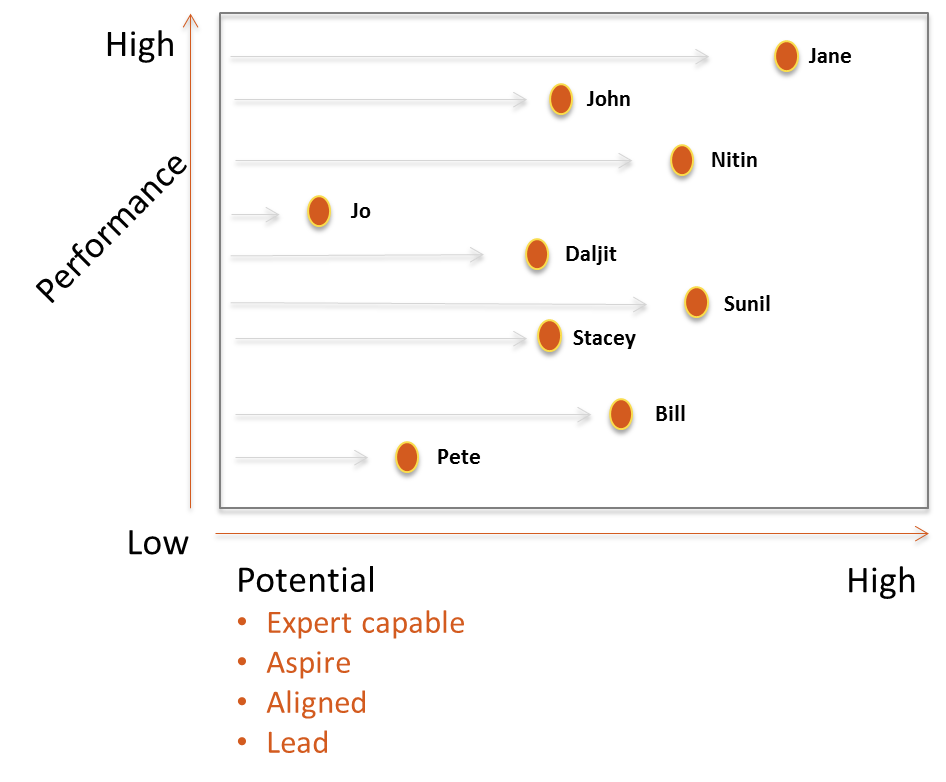

Step 1: Build a grid with 2 dimensions: Performance and Potential.

Step 2: Rank order your team in terms of performance along the performance dimension. Do this without regard to issues of seniority. Treat the team as a single homogenous population.

Step 3: Position each team member on the grid in terms of their demonstrated potential. In doing this you would consider how the 4 drivers of potential are being demonstrated by the person. This will ensure that subsequent messaging can be specific and targeted.

Step 4: Draw 2 lines on the grid creating a zone of intolerance around performance and a zone of intolerance around potential. These zones have been created by effective practice leaders to allow them to optimise their time use in leading their teams.

The best place for a leader to spend their precious leadership time is with people in the solid core and with their stars

Yet low performers and people who are not aligned to the firm tend to cause issues and create events which soak up available management time. In these zones you can create policies and principles that allow you to quickly deal with people within them.The best place for a leader to spend their precious leadership time is with people in the solid core and with their stars.

Each firm will be different in the policies they develop, but for example if a person was low in performance, a policy may be ‘6 months to improve and if not we will start to decide over the next 6 months what you may do next in your career outside the firm’.

A policy around low potential may be: ‘you will never be promoted or progress if you stay here’. These zones make the deal predictable and actionable.

Step 5: For each person named on the grid, develop 2 sets of messages. A calibration message – How is the person doing against your expectations of them and relative to the performance of the team itself.

Secondly, build a set of development messages. We have found in our work with firms that these messages tend to relate mostly to the work or to the clients and are about providing the person an opportunity to grow by stretching themselves around new professional experiences (always related to the strategy and core competence of the firm).

So for example a senior fee earner who is both high performing and high potential may be given the opportunity to run a complex new piece of work and a set of potential clients to go and win. An early career professional in the same grid position may be challenged with new types of work and a first go at managing others. Bearing in mind the 1st rule of stretching and improving performance: as a leader you must always match the degree of challenge with a balancing level of support. High challenge also means high support.

Step 6: Tell the people: Up until now we have been discussing conceptual or intellectual issues of talent identification. But of course the impact in this type of exercise is only apparent when the people who are affected by it know how they are doing and what they should do as a result. In our research we have been able to test this condition by simply asking the fee earning professionals if they understand their current performance and future development opportunities. In every case where we have found this technique to be effective in accelerating the development of professionals, we have also found that the partners and senior fee-earners have been effective at giving their people direct and clear feedback. They have been both skilled and brave enough to talk to their people about the things that matter to them in their careers.