A new manager is recruited to turn around the performance of a poorly performing team with low morale. Is there a sequence of actions that the manager should take in order to improve the performance of a team? How should poor motivation and disorganisation be dealt with?

The relationship between performance and morale

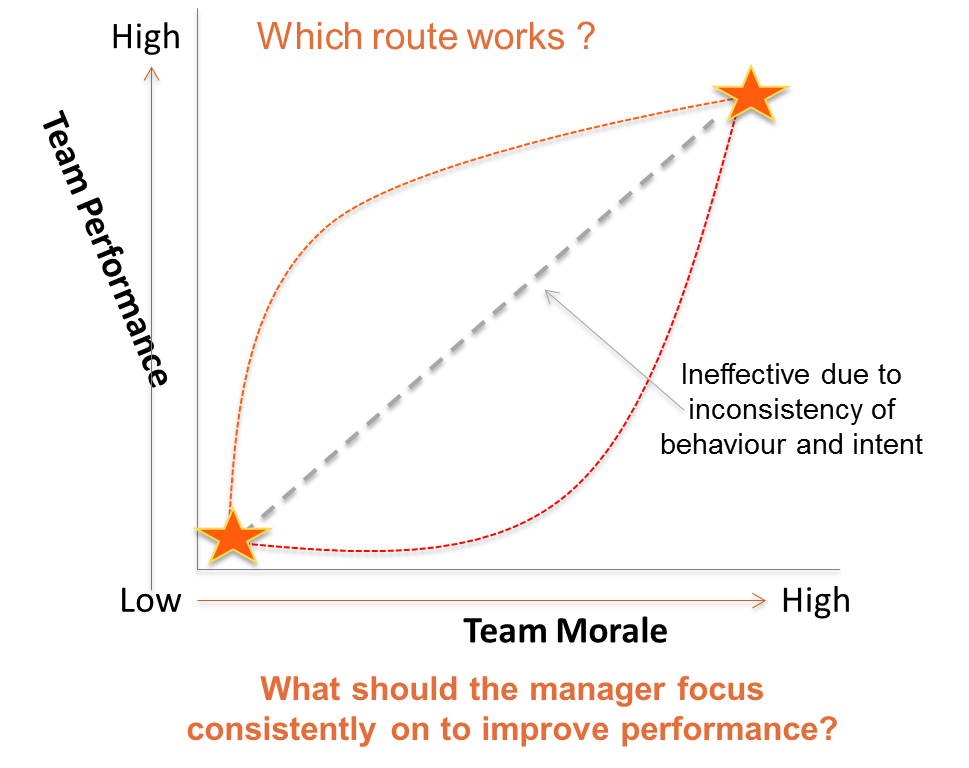

The first principle in performance improvement is that the manager must be consistent in both behaviour and intent. Inconsistency leads to confusion. The team must be able to predict how their effort and performance will be judged. If the manager behaves inconsistently, prediction becomes difficult and performance does not change. This leads to just two routes to sustained performance improvement: a consistent focus on improving morale or a consistent focus on directly acting on performance. (See figure 1)

Figure 1: Two routes to performance improvement- which do you follow?

Given this issue, the manager is faced with a fundamental question:

Will making a team happy (in their underperformance) cause them to improve or will focussing directly on performance improvement create a situation whereby morale improves as performance improves?

Does having high morale cause high performance or does high performance cause morale to improve?

As ever, when dealing with real people in real jobs, the answer is never simple.

What is clear, however, is that people respond differently to increasing levels of challenge!

People who have a higher than average need for achievement and who are prepared to accept challenging goals will experience increased commitment and motivation when their efforts prove to be successful. These people will upwardly re-define their goals and aspirations as long as they continue to receive what they believe to be adequate recognition and support from their leaders.

Others in the team, whose need for achievement is less, will experience the layering on of challenge as uncomfortable and their effort and commitment will diminish.

It is commonplace to find high performing teams in which most if not all team members are satisfied in their roles.

It is also common to find satisfied teams whose performance is not above the average. The conclusion must be that on balance, performance drives morale in those people who managers would want in their high performing teams.

For the practising manager, this leads to hard choices.

The harsh reality is that for the team to be high performing it needs to be populated with high achievement-oriented individuals who will accept, even relish, increasingly challenging goals.

For the high achievers, the satisfaction of strong performance and the vicarious satisfaction of colleagues who are equally as good, leads to ever-increasing performance. So our new manager needs to be tough enough to make the call on people who don’t meet the performance standards that are being set by the team itself!

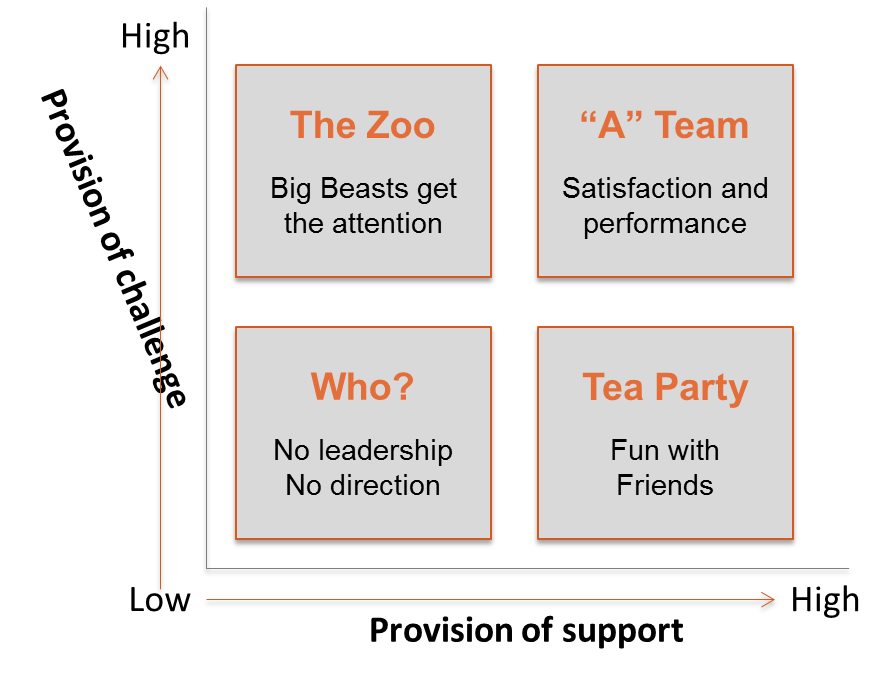

However, high performing team members also make high demands of the team leader. They need high levels of visible support, recognition and loyalty from their manager, who also needs to be seen as representing their interests around the organisation. Figure 2 explores the balance that needs to be maintained between exposing a team to challenge and providing support.

Figure 2: The provision of challenge and support

First steps to take

To build a pathway to high performance, first of all, you have to understand the purpose of the team. In a commercial organisation, this purpose is to provide value to its customers and clients. This may be to an external customer, but also maybe to other teams or leaders within the business. First steps to take

Teams which are seen by their clients and internal leaders, as high performing are always clear about their purpose. The team structures, processes and focus of effort are clearly directed towards achieving it.

This point may seem obvious but in many organisations, the role of a team is confused.

The team has many conflicts and political constraints that confuse and dilute its purpose. It is surprising how many organisations live with this confusion and tolerate under-performance at both the team and individual level. A clear purpose leaves nowhere to hide and this can be threatening for many people. It is certainly not unknown for managers to collude in creating confusion of purpose to avoid this exposure.

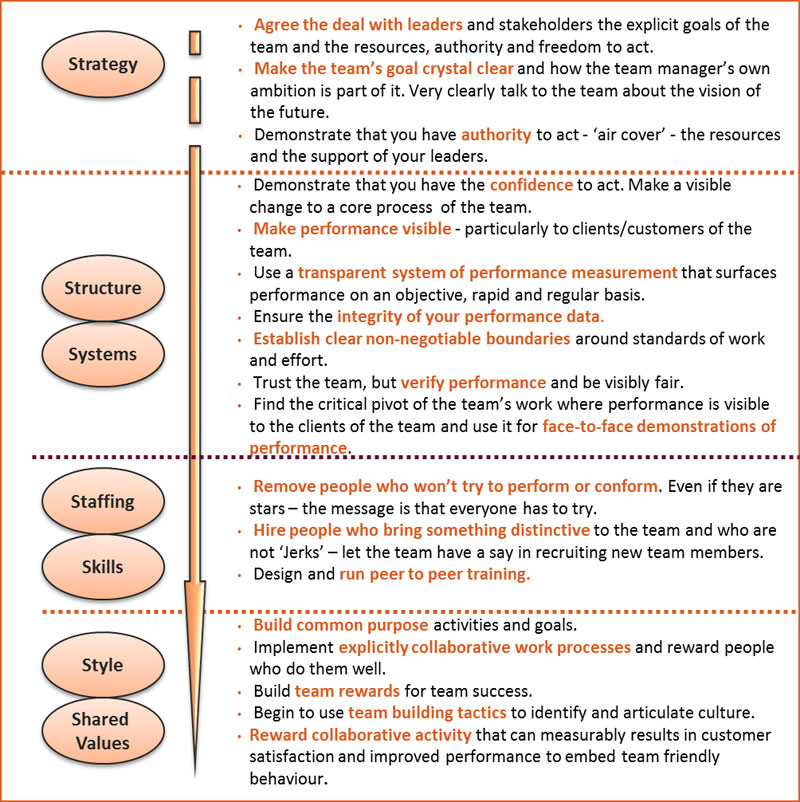

The first step that our manager needs to take is to negotiate with leaders and stakeholders, a clear team purpose with specific goals. The new manager must also have the resources, freedom and authority to make the necessary changes to the team.

Don’t take the job if you can’t do this! Failure at this point invariably means that the team is left open to re-interpretation of its goals by vested interests around the organisation and team effort is directed towards the loudest complaints or the smartest manipulators.

Deciding what needs to change

A critical characteristic of high performing teams is that everything they are and everything they do is aligned to the purpose and goals of the team. The more tightly aligned a team, the better its performance,

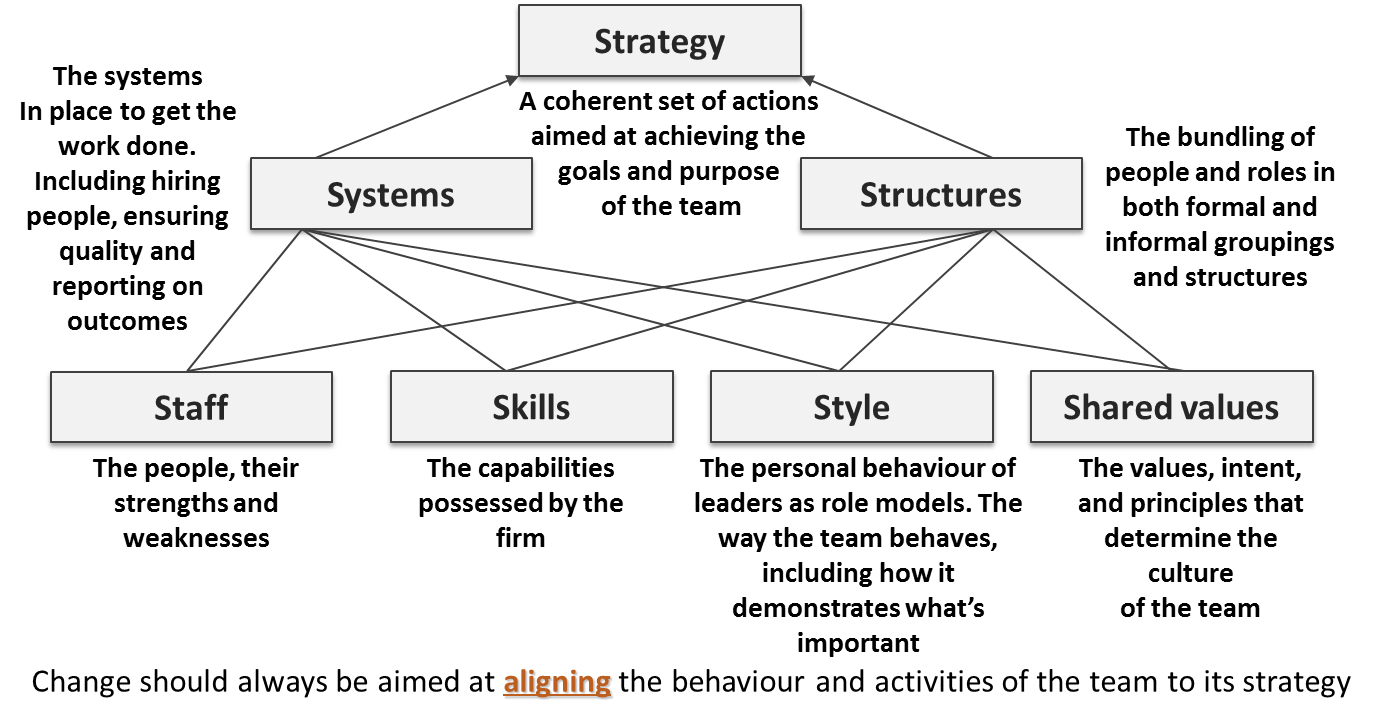

One well-tried and tested way of building alignment is to use a diagnostic framework which links the team’s purpose and goals to all the other elements one needs to consider.

The McKinsey 7s framework is an ideal tool to use to do this (See figure 3). Based originally on the book by Peters and Waterman: In Search of Excellence; the 7s can be used to work systematically through every aspect of a team’s activities and behaviour with the aim of creating alignment to the purpose of the team.

The analysis should determine what the team needs to change, improve or eliminate to maximise the degree of alignment.

Figure 3: The McKinsey Alignment Framework (The 7s Model)

However, the elements of the 7s model should not be tackled all at once. Also notice that a change in one element creates the possibility for a change in all of the other elements.

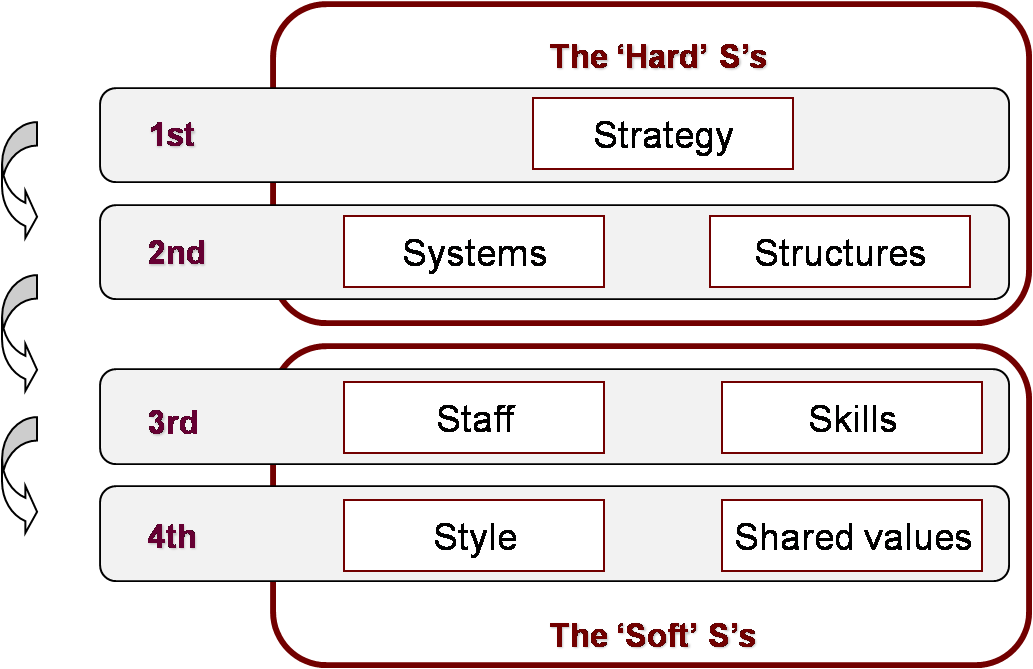

There is a definite order in which changes that affect alignment should be tackled. Practitioners break the 7’s into 2 categories: ‘hard’ S’s and ‘soft’ S’s.

The ‘hard S’s can be actioned directly by management decision and directly affect the focus and boundaries of team activity. The ‘soft’ S’s require engagement and commitment from team members. As a result of this, a manager can have a more immediate impact by concentrating on the hard S’s of strategy, structure and systems. See figure 4 below which sets out the sequence through which change can be driven.

Figure 4: The order of implementation of the 7s Model

Measure everything and agree goals

If the team has crystal clear goals that are agreed and accepted by the organisation, then one of the first things a team leader needs to do is to find ways of measuring progress.Measure everything and agree goals

It is no accident that many high-performance teams have developed rich, transparently fair and objective means of measuring team and individual performance.

As the team starts to make visible progress, the aspirations of high achievement team members will grow. The existence of objective measures creates a situation where the manager does not need to spend time debating different opinions about performance; it exists as an objective fact. Therefore the manager can spend time focussing on improvement tactics and coaching around the agreed solutions.

In these conditions, it becomes possible for the manager to help people to begin to stretch themselves and their capabilities and agree progressively more stretching goals and performance targets.

It is important to note that these stretch targets are not being imposed on people! They are emerging from a growing sense of confidence in the team itself. The manager is not setting goals; they are generated from the team and agreed by the manager – a bottom-up process, but one that is rigorously applied. Performance of the team improves, not because people are being whipped into action, but because they are excited and energised about what they can achieve.

Expose performance to the customer

The work of every team eventually reaches a point or a few points where the quality or appropriateness of the team’s effort is directly exposed to its clients. It is at this pivotal point – a ‘moment of truth’ that performance is judged.

The key is to expose team members to the direct performance feedback of the client or customer. Systems of feedback capture should be found which are rich in information and delivered to the individuals and the team as near as possible to real-time. Failure or under-performance should be objectively and cleanly exposed. Activity-based performance targets or standards should be directed here. Coaching and training should be focussed at improving at this specific point.

The effect of doing this will be to differentiate between team members who are willing to up their game and who get a positive thrill from improvement on the one hand; and on the other, those people who will move into defensive postures or disengage.

The leadership challenge of high performance

So what does it take for a leader to successfully drive a team to high performance? The volume of research into team leadership is vast and complicated by fad and fashion. However, there are a number of aspects of leading teams that are very clear.

- Successful team leaders are seen to have a passion for the work. Success for the team and for themselves is visibly important to them.

- Successful team leaders demonstrate a willingness to be intolerant of outcomes or behaviour that falls below what is expected.

- They are seen as ‘tough’ (but fair) in dealing with individuals who don’t perform or conform to team values. Typically they do this in a straightforward and immediate way. Feedback from them is seen as fair, objective, constructive, in real-time and with no ‘beating about the bush’.

- They are typically offering high levels of help to the underperforming individual but are able to move smoothly to ‘counselling out’ if improvement does not occur

- They also hold themselves to the same standards of effort and results. They have a ‘do as I do’ mindset– not a ‘do as I say’ mindset and are visibly willing to get into the trenches with the team. Through their motives, principles, behaviour and commitment they act as aspirational role models to the team.

- They both give and expect a high degree of loyalty from team members, once the team has proven they can deliver the expected quality of effort and result. Successful leaders are often seen standing up for their people in the face of what they see as the unreasonable demands or opinions of others, even more, senior managers.

- They demonstrate a ‘coaching’ style of interaction with team members, spending a significant amount of time in helping them to set goals and targets and to work with them in developing solutions and action plans.

Importantly, the leader’s success can be seen in the affective outcomes of their interactions with their team. Successful team leaders tend to be people who cause others to experience themselves as energised, committed and confident. Team members gain energy from their interactions with the leader. They gain confidence and this translates into higher levels of effort and commitment.

Two critical questions a leader should ask themselves everyday

· How do people experience you?

· How do people experience themselves in your presence?

People who cause others to experience themselves as energised, committed and confident are most likely to be seen as leaders

Build ‘Bench Strength’ to keep improving

With objective and transparent performance measurement systems in place, weak individual performers will leave the team and need to be replaced. These events are to be seized as a means of improving the capability of the whole team, by hiring newcomers who bring the following characteristics:

- A history of good performance.

- Achievement motivated.

- A dominant and distinctive skill that is better or additive to the existing team skills.

- Someone whom the rest of the team feel they can work with.

This last characteristic means that it is important to include team members in the selection of their future co-workers, as it ensures the new joiner will be inducted into the team by people who have already acknowledged the person’s value and have a stake in their success.

A second opportunity to build bench strength is through training and learning. The question is who should people in a high performing team turn to in order to learn new skills and new knowledge that the team needs to improve? The answer is each other! Team ‘self-training’, either through informal briefings, peer-to-peer coaching or formal training programmes are a very common feature in strong teams. Team members readily recognise who amongst their members have particularly strong specific knowledge and skills and the team manager can make very good use of this as a means of creating recognition for the individual by using them to teach others in the team.

So what does come first?

If we return to our question posed at the beginning of this article;

What should a manager focus on to turn around a badly performing team with low morale?

There are two realistic choices; one is to initially focus on the morale of the team: make them feel better about themselves, grow their sense to be in a team and tell them they can achieve great things.

The second option is to first set the direction, goals and performance standards expected of every team member, relentlessly drive performance, remove waste, inefficiencies and disaffected team members and reward those whose performance improves.

Figure 6: Building Team Performance – Hard then Soft

The answer is unequivocally to focus on the hard stuff first (see figure 5) – Set the standards. Drive-up performance. Be relentless. Be prepared to lose people who can’t or won’t achieve. Once this context of performance has been deeply embedded, then move from good to high performance by using the confidence and aspirations of achievement-oriented individuals who are doing well, to bind the team into further performance improvement through the synergistic benefits of teamwork and shared commitment. Make acting as a mutually supportive team a basic shared value and further reward the people in the team who do this well.

The path to high performance There is a tried and tested pathway to high performance for a team leader with high achievement-oriented people, who can simultaneously maintain and improve hard performance standards on the one hand while operating as a visibly fair, supportive, coaching based leader on the other. Figure 6 is a summary of the steps to take to build a high performing team. The path to high performance

Figure 7: The path to high performance

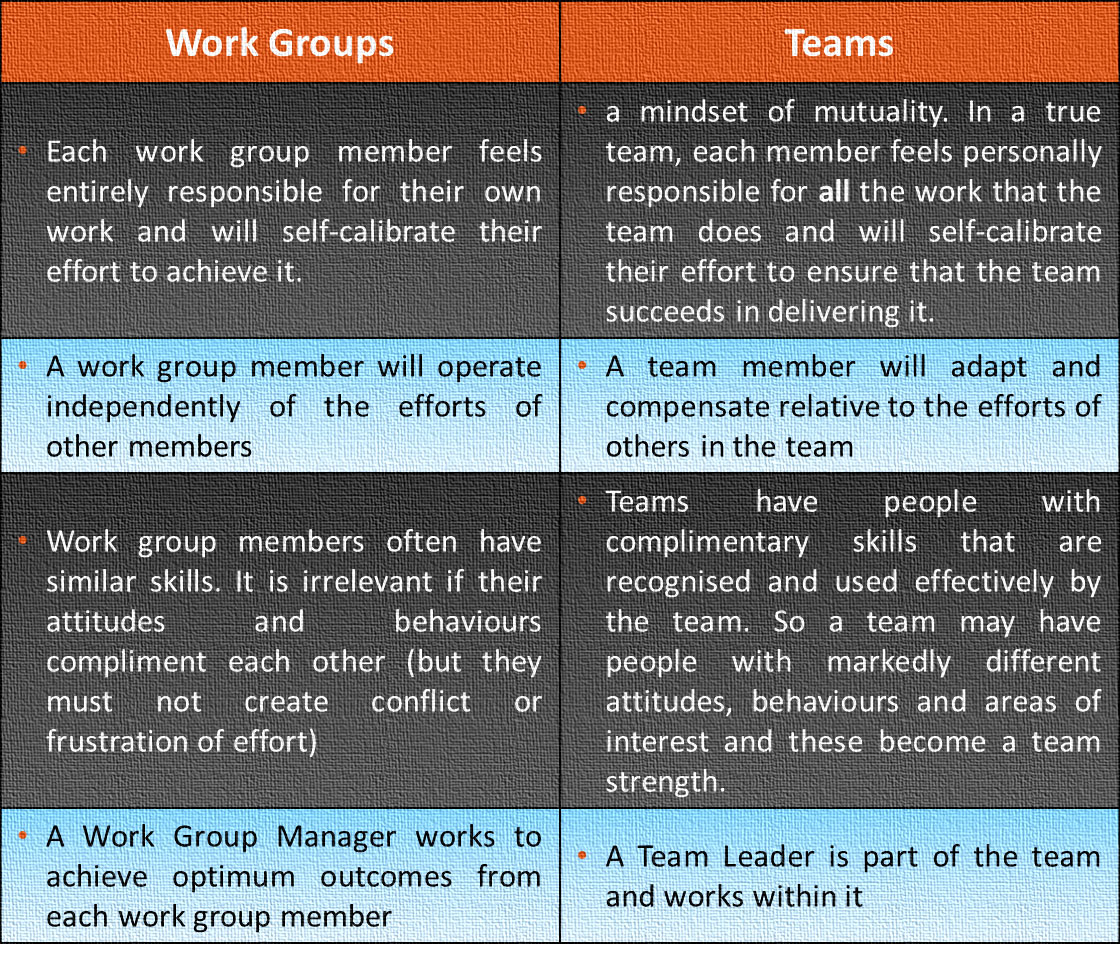

One Final Thought – Do you really need a team?

A question one should consider in building team performance is, whether or not one will actually achieve higher performance by asking people to work as a team?

- There is a tendency in organisations to describe every department or workgroup as a team and assume that teams are a silver bullet to better performance. However, teams are complex organisms. They require a lot of feeding and nurturing and in many cases, the effort and resources required to do this outweigh the rewards.

- In many cases, the individuals delivering the work would actually benefit from less team activity, fewer meetings and less need to communicate with others so that they can focus more time and effort on their work and satisfying their customers.

- It may well be that one is dealing with a community of workers who share similar overarching work goals but who have distinctive and different constituencies of clients or stakeholders. They may need to share knowledge and occasionally or even regularly collaborate – but that doesn’t make them a team. The reality of this situation has a major impact on the specific tactics a manager would use to improve performance. Teams work because the work itself requires the sustained and collective effort of a number of people with different skills and abilities, collaborating to deliver a superior result.

- If the work of the ‘team’ doesn’t look like that then the management tactics would need to change to reflect this. If the answer is – yes, it is a team! Then teamwork must become a dominant value amongst the team members. Lone rangers are not allowed here. Behaviour that does not support teamwork is not tolerated by management. Work processes and systems are specifically designed to cause people to collaborate and quality performance as a result of teamwork is rewarded.